Edible Forest Gardening

Basics

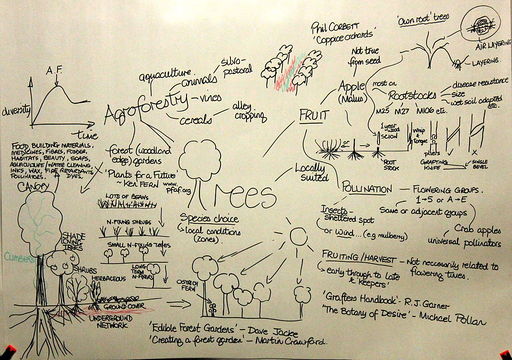

Imagine you are walking through a green leafy forest with trees hanging over you, shrubs and ground cover around your feet, small woodland animals rustling in the undergrowth. It is an ordinary wild forest, but it is also something more, because this forest has been designed to be maximally productive for humans. The trees bear fruits and nuts, the ground cover and bushes grow berries, the wood is useful for building houses, furniture and art. this is the aim of forest gardening or agroforestry.

In 2005, Dave Jacke, Eric Toensmeier and numerous people 'behind the scenes', provided a new framework from which to consider forest gardening. Their seminal two-volume work, Edible Forest Gardens - Ecological Design and Practice for Temperate Climate Permaculture, has offered a body of in-depth analysis for temperate climate forest gardening and set the stage for future studies and advancements in this largely unexplored field.

Forest gardening is an ecological design practice that mimics the patterns of natural forests. It does this by incorporating the whole vertical span of the forest - from the canopy level, to the understorey of ephemerals and medicinals, to the interactions at the micro-organismic level of the soils, and the whole temporal span of the plants from perennial to annual-mixed plants.

However, there is a clear distinction between gardening like the forest and gardening as the forest. Because one is designing for human-accessible and abundant yields, one is mimicking forest patterns for human good. This has indirect beneficial impacts beyond the human level - i.e., animal and insect habitat, revitalized soil beds, water capture etc.; both the good of humans and the good of other species are served. A successful forest garden creates effortless abundance for people. Though work is needed for the first few years, once the ecosystem is established, it becomes more and more rich without human intervention.

Forest gardening is modelled after what ecologists have learned from succession studies:

"Succession studies show that patches are fundamental organizational units in natural ecosystems...to create structural diversity, we should respond to and mimic this patchy reality"

~Edible Forest Gardens - Volume 2 (p. 10)

With this in mind, the forest gardener is urged to imagine an ever-changing forest garden. This often entails a 'whole-istic' design process projecting successive stages of a forest garden. Consequently, one can begin their design process by modelling an 'end' stage of succession; tracking backward through a mid-successional stage; and installing (or planting out) their first trees, shrubs, and plants mimicking the pioneer stage of early succession.

Videos

Robert Hart's Agroforestry (at 14:10 Robert Hart answers the question of how to start a forest garden from scratch)

Ethan Roland discusses Oak, Currant, Raspberry, Sedum polyculture:

Ethan Roland updates forest garden progress at Epworth Permaculture Center

How to

An edible forest garden can be divided into vertical storeys:

- Tall trees are at the top. Edible examples include most kinds of nut tree and mature fruit trees.

- Short trees form the layer below that. Edible examples include apple and pear trees and dwarf varieties of all fruit and nut trees, or fruit trees grafted onto rootstocks that will keep them small.

- Below the trees is the shrub and bush layer. Edible plants in this layer include berry bushes of all kinds.

- Herbaceous plants, including all the edible kitchen herbs like parsley and rosemary are next.

- Horizontally spreading ground cover form the lowest layer off the ground. Edible examples include lingonberry and some kinds of strawberry and raspberry.

- The lowest layer is the root crops, consisting of all those plants whose edible portion grows underground. Examples include potatoes, ginger and taro.

- And lastly the vertically-growing class of vines and climbers. Edible examples include runner beans, kiwis and cucumbers.

The tallest trees should be planted first, spaced apart. Fruit trees from a nursery would normally be used. The the other layers are planted in between these trees.

The ground needs to be well mulched at first, when the trees are young and vulnerable to being outcompeted by weeds. Once the forest is mature, after about two years of cultivation, there is hardly any need for maintenance.

Having bee hives in the forest is certainly a good idea.

Concepts

(in no particular order - these concepts are adapted from Dave Jacke's Edible Forest Gardens - Volume 2 and my own experiences.)

Preparing the site: Particularly in areas with 'poor' or compacted soil - often the results of previous agricultural monocropping. This will include anything you aim to accomplish prior to planting out your forest garden BUT should also be considered seriously if the healthy establishment of a young forest garden is in question. This practice can greatly improve the health of your forest garden as well as its yield capacity. It will also minimize future work - if you simply plant your forest garden without attention to its soil quality you are creating unnecessary competition... both for scarce nutrients and with a pre-existing 'weed' seed bank.

Most poor soils can be improved by adding organic materials and/or breaking up hard-panned and compacted soils with deep-reaching perennial root systems. However, it is also beneficial to work with beneficial annuals. For example, Yellow Sweet Clover (Melilotus officinalis) is an introduced annual or biennial whose root system extends as far down as 20 feet. Plants like this stabilize the soil and act as dynamic accumulators during the early years of a young forest garden. This plant is often used in organic agriculture rotations as a cover crop. It can also be used in combination with a fast-growing grain crop for livestock feed over winter months. This past season, at Mark Shepard's New Forest Farm we covered an acre with millet and yellow sweet clover. The results: the livestock (3 holstein bull calves) received a healthy 3-5 round bales of millet/clover and the yellow sweet clover will grow back in spring adding continued soil stability during southwest Wisconsin's rainiest months. Ideally, one could feed 3-5 heads of livestock by performing this strategy on 2 to 3 acres. Back to the forest garden...

It should be noted that to correctly determine a given site's desired dynamic accumulators a series of soil tests and subsoil tests should be considered. Regardless, one ought to consider growing swaths of 'mulch plants'. i.e.,stinging nettle, comfrey, sorrels and docks, vetches etc that will uptake trace elements. These patches can be harvested and mulched or composted - either in a compost pile or in a fermented compost tea.

An interesting idea I have considered lately is the dual combination of composted 'weeds' in tea form (i.e. nettle, comfrey et al) with coppice-able dynamic accumulator trees (basswoods, birches, hickories, black walnut et al). In this manner one could create a fermented and slightly aged mulch material - a layer of organic materials providing many functions in a forest garden.

For detailed analysis on species lists applicable to this concept see Appendices 2 and 3 in Dave Jacke's Edible Forest Gardens - Volume 2, Design and Practice pp. 524-536

Internal Links

- Permaculture

- Forest

- Forest Garden Greenhouse

- Edible Landscaping (A similar concept but on the level of individual buildings)

External Links

- The Wikipedia Page on Forest Gardening

- http://www.edibleforestgardens.com/about_gardening

- Martin Crawford's 1995 series "Fertility in Agroforestry & Forest Gardens" in Agroforestry News.

- Martin Crawford"Creating a Forest Garden: Working with Nature to Grow Edible Crops"

- Robert Kourik - Designing and Maintaining Your Edible Landscape Naturally. 1986.

- Lawrence Hill - Comfrey: Past, Present, Future. 1976.

- http://www.oly-wa.us/Terra/Sansone.php (broken link?)

- Establishing a Food Forest The Permaculture Way - instructional video.